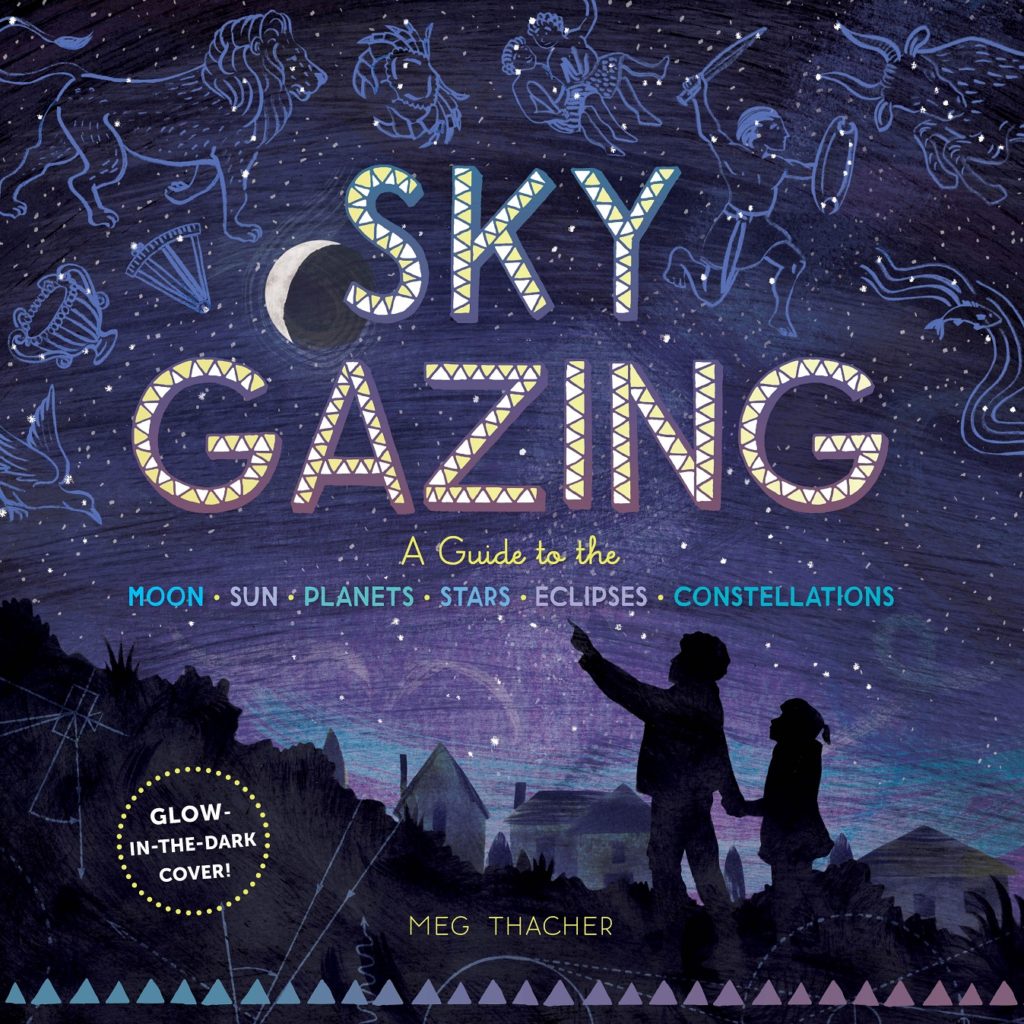

I’m very excited to welcome fellow New England SCBWI member Meg Thacher to the blog to celebrate the release of her STEM non-fiction children’s book STAR GAZING: A GUIDE TO THE MOON, SUN, PLANETS, STARS, ECLIPSES, AND CONSTELLATIONS. I was very lucky to get an early copy (and the boys were super excited to check it out) and you can read my 5-star review on Goodreads.

Star Gazing: A Guide to the Moon, Sun, Planets, Stars, Eclipses, and Constellations had a bit of an unusual path to publication. What were the circumstances of how you came to write the book?

One day I got an email from Deb Burns, an acquiring editor at Storey Publishing, asking if I’d be interested in writing a book about astronomy for kids. It seemed completely out of the blue, but Storey’s model is to find experts to write books about what they’re experts in. I teach astronomy at Smith College, and by that time I’d written 19 articles for kids’ magazines. So I also had a track record of writing for kids, working to spec, and (mostly) meeting deadlines. Deb and I wrote the book proposal together, she pitched it to her editorial team, and we got the green light. So I highly recommend writing for magazines—it’s a great way to break into the business!

The design of the book is beautiful and it’s filled with so many fun little tidbits. How collaborative was the process of making the book?

Very collaborative. Along with my manuscript, I provided Storey with a list of suggested illustrations—photos, figures from the internet, and little sketches I’d made by hand or (I’m totally serious here) with Powerpoint. After Deb and a copy editor spiffed up my manuscript, my amazing book designer (Jessica Burns) took over. Storey hired an illustrator (Hannah Bailey) to do the diagrams, pictures, and amazing graphic novel sequences. It took three draft layouts and two in-person meetings to get to the final product (this was BC, before COVID). My main job during this process was making sure everything was scientifically accurate. Hannah’s illustrations look SO much better than my sketches, and Jess is just a wizard of putting text and illustrations on a page so that they make sense.

What is your favorite part of the writing process? What is your least favorite part?

I love everything about the writing process except actually writing! I’m a plotter, so I outline like crazy—the only way I can write nonfiction is to know where I’m going at all times. I am a research nerd, of course. And I really like to revise: it’s so satisfying when I find the perfect word or turn of phrase. But my first drafts? Blech.

What is next for you in your writing career? Do you have an upcoming releases or a favorite project you’re working on right now?

No upcoming releases yet. I’m working on a middle grade informational fiction book about a 5th grade girl who loves astronomy. And like all children’s writers, I have a computer folder full of picture book manuscripts that are slowly making the rounds.

And finally, what is something funny/weird/exceptional about yourself that you don’t normally share with others in an interview?

I’m a really good swimmer. I was never on a swim team, but I lifeguarded and taught swimming from age 18 to 24. I can keep up with people who are in much better shape than I am because I have good form and an efficient stroke. (Just don’t ask me to do the butterfly!)

STAR GAZING blurb:

Sky Gazing is a guide to observing the sky from wherever you are, day or night—no telescope required. Kids aged 9–14 will learn how to find objects in the sky and delve into the science behind what they see, whether they live in a dark rural setting or under the bright lights of the city. Star charts will guide them in spotting constellations throughout the seasons and in both hemispheres while they learn about constellation myths from cultures around the world. Each chapter has guides to special events and binocular observing. Activities engage kids and their grown-ups in hands-on science.

Buy the book on Amazon, IndieBound, Better World Books, or Barnes & Noble.

About the Author:

Meg Thacher has been writing for children’s magazines since 2013, publishing thirty nonfiction features, infographics, scientist profiles, current events, DIY experiments, and a reader’s-theatre-style retelling of a Welsh folktale. Her debut book, Sky Gazing, comes out on October 13. She’s an active member of SCBWI (the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators) and two critique groups. She is now in her twenty-second year teaching astronomy at Smith College, where she has also taught writing. She enjoys singing, knitting, and swimming, and lives in a partially empty nest in western Massachusetts.

Website: megthacher.com

Twitter: @MegTWrites

Facebook author page: https://www.facebook.com/MegTWrites